What Is Mission Theology?

The introduction will briefly define what mission theology is and then proceed to examine five of its essential characteristics: mission theology seeks to be multidisciplinary, integrative, definitional, analytical, and truthful. But first a note regarding the rise of mission theology as a separate discipline.

For the past thirty years mission theology has taken a backseat to mission practice, which, after the two world wars and particularly in the 1960s, began to borrow heavily from the social sciences: sociology, anthropology, linguistics, economics, politics, statistics, sociology of religion, and so forth. Whether Roman Catholic, Orthodox, conciliar, evangelical, or

Pentecostal/charismatic, the major missiological agendas that dominated the

scene after the early 1960s dealt primarily with the strategy and practice of

mission. Regardless of the theological tradition, missiology concerned itself with a host of activist issues and agendas like the role of the church (its clergy, structures, and members) in the mission enterprise, relevant economic and sociopolitical

action, liberation, evangelism, church growth, relief and development, Bible

translation, theological education, mission-church partnerships,

church-to-church sharing of resources, dialogue with people of other faiths, and

the relation of faith and culture. Unfortunately, in the midst of such busy global activism, the deeper questions of mission theology were too seldom asked. During the last ten years this has begun to change, and people of all theological stripes in mission today are reexamining theological presuppositions that underlie the mission enterprise.

The discipline that reflects on these presuppositions is theology of mission or mission theology.1 Prior to the 1960s, a number of prominent thinkers like

L/

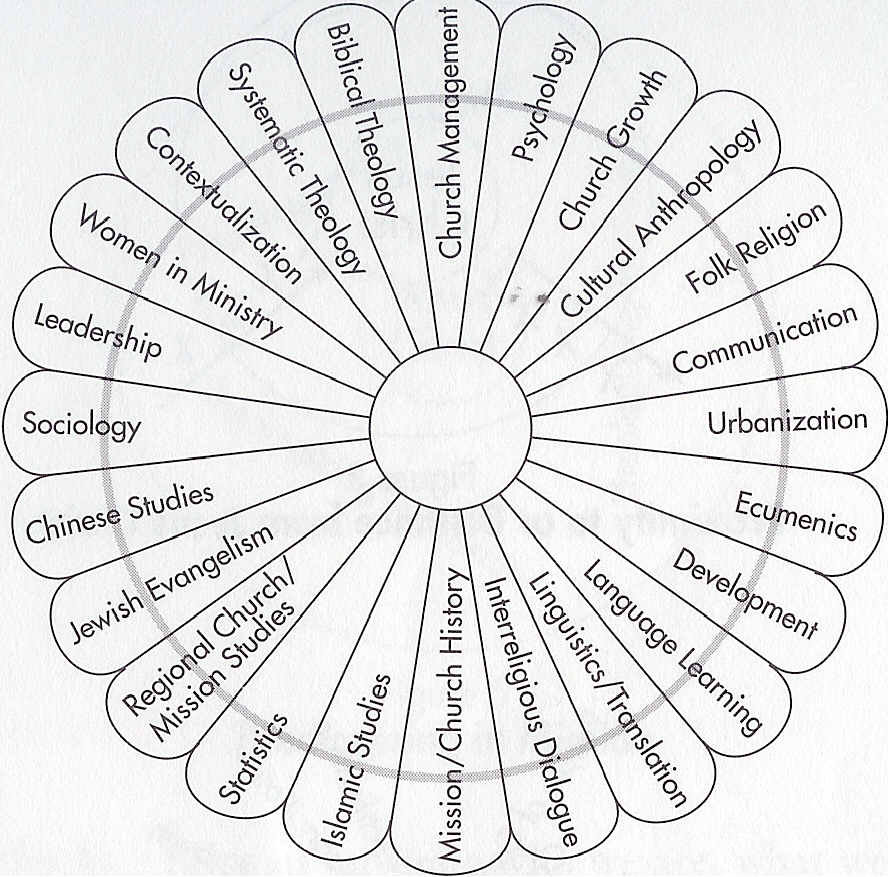

Figure 1 Missiology as a Discipline

Gisbert Voetius, Josef Schmidlin, Gustav Warneck, Karl Barth, Karl Harten- stein, Martin Kahler, Walter Freytag, Roland Allen, Hendrik Kraemer,

J. H.

Bavinck, W. A. Visser't Hooft, Max Warren, Olav Myklebust, Bengt Sundkler, Carl Henry, and Harold Lindsell reflected on the theological issues of mission. However, if we seek to find theology of mission as a separate discipline with its own elements, methodology, scholars, and focuses, we find that theology of mission as such really began only in the early 1960s through the work of Gerald Anderson. In 1961 Anderson edited The Theology of the Christian Mission, a collection of essays which I consider to be the first text of the discipline.

Ten years later, in the Concise Dictionary of the Christian World Mission, Anderson defined the main concerns of theology of mission as "the basic pre- suppositions and underlying principles which determine, from the stand- point of Christian faith, the motives, message, methods, strategy and goals of the Christian world mission. . . . The source of mission is the triune God who is himself a missionary. . . . In this 'post-Constantinian' age of church history, mission is no longer understood as outreach beyond Christendom, but rather as 'the common witness of the whole church, bringing the whole gospel to the whole world'" (Neill et al. 1971,594).2

Mission Theology as Multidisciplinary

Mission theology is a difficult enterprise because its object of reflection is

the entire field of missiology, which itself is a multi- and interdisciplinary

enterprise. For the sake of brevity, this section will graphically represent and simply

state a series of short propositions that describe the multidisciplinary enterprise that is missiology and the way mission theology interfaces with it.

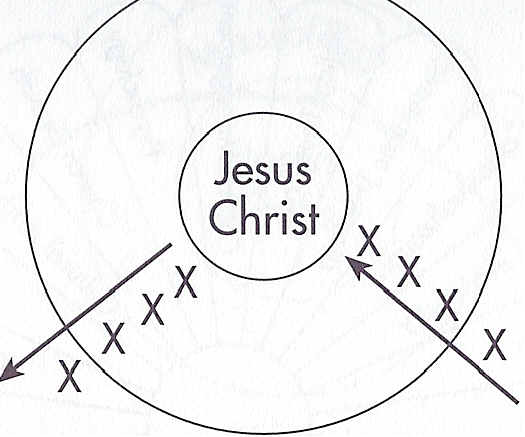

Figure 2

Missiology

as a Multidisciplinary Discipline

1. In the first place, missiology is a unified whole; it is a discipline in its own right, centered in Jesus Christ and his mission (see figure 1). As the church participates in the mission of Jesus Christ, it participates in God's mission in God's world through the power of the Holy Spirit.

2. While missiology is known to be a unified discipline, it is also a multi- disciplinary discipline (see figure 2). As a multidisciplinary discipline, missiology draws from many areas of skill, cognate disciplines, and bodies of literature.3

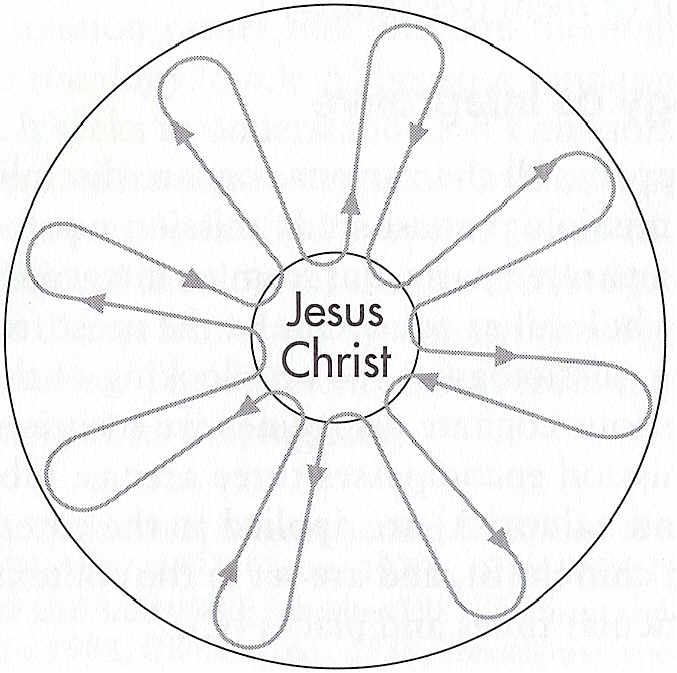

Figure 3

Proximity

to or Distance from Jesus Christ

Figure 4

The Integrative Center (MISSING)

3. Mission theology helps us clarify our proximity to or distance from the center, Jesus Christ (see figure 3), and asks whether there is a point beyond which the cognate disciplines may no longer be helpful or biblical.

4. Mission theology helps us reflect on the central idea (the habitus) which

integrates and motivates our missiology (see figure 4).4

Figure 5 Theologizing in Mission (MISSING)

5. Mission theology helps us integrate who we are, what we know, and what we do in mission. It helps us bring together and relate to the cognate disciplines of missiology our faith relationship with Jesus Christ, our spirituality, our consciousness of God's presence, the church's theological reflection throughout the centuries, a constantly new rereading of Scripture, our hermeneutic of God's world, our sense of participation in God's mission, and the ultimate purpose and meaning of the church (see figure 5).

6. Mission theology helps us move continually between the center and the outer limits of the multiple cognate disciplines of missiology as we constantly

seek integration, deepened understanding, and mutual enrichment of the various disciplines as one discipline-missiology (see figure 6).

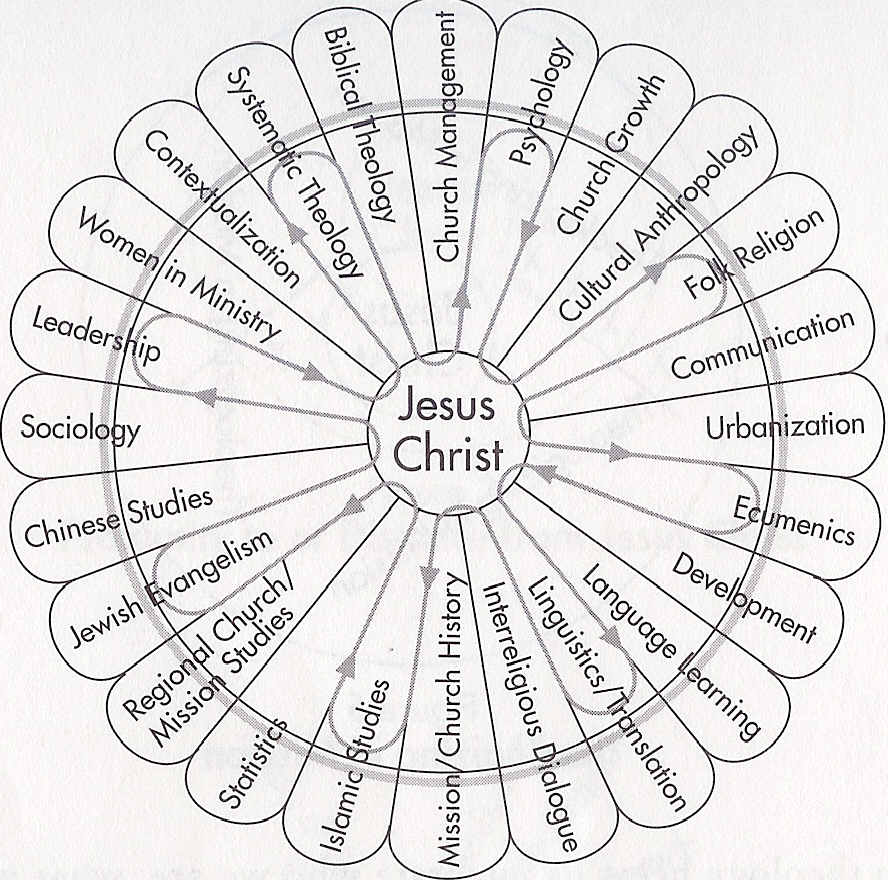

Figure 6 Mission Theology

7. Mission theology serves to question, clarify, integrate, and expand the presuppositions of the various cognate disciplines of missiology. In doing so, mission theology is a discipline in its own right, yet it is not merely one of the petals alongside the others, so to speak, for it fulfils its function only as

it interacts with all of them (see figure

7).

Figure

7

Mission Theology in Missiology

Mission Theology as Integrative

When mission happens, all the various cognate disciplines are occurring simultaneously. So missiology must study mission not from the point of view of abstracted and separated parts, but from an integrative perspective that at- tempts to see the whole all at once. One of the most fruitful ways to do this involves perceiving missiology as the interlocking of three circles that bring together all the various cognate disciplines we mentioned above (see figure

8).

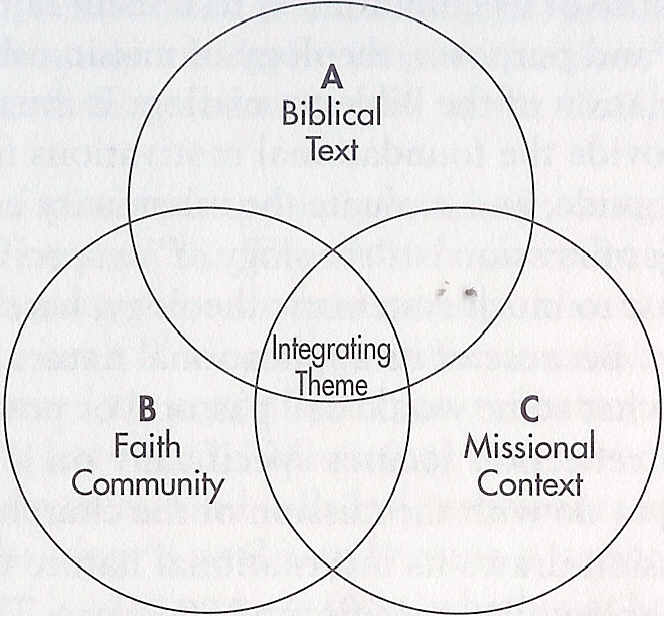

Theology of mission encompasses three arenas: biblical and theological

presuppositions and values (A) are applied to the enterprise of the ministry and mission of the church (B), and are set in the context of specific activities

carried out in particular times and places

(C).5

Figure 8

The Tripartite Nature of Theology of Mission

The reader will see that the three circles are brought together by means of an

integrating theme that constitutes the central idea interfacing all three circles. The integrating theme might be the people of God, reconciliation, the cross, compassion, church growth, or the glory of God (for other examples see figure 4). It is selected on the basis of being contextually appropriate and significant, biblically relevant and fruitful, and missionally active and trans- formational. It will help hold our various ideas together-particularly when we are moving from circle A to circle B, that is, from a rereading of Scripture to praxeological action-reflection in order to discover the missiological implications of our rereading of Scripture.

To explicate the three-arena nature of the discipline, it will be helpful to speak of theology of mission rather than mission theology. First, note that theology of mission is theology (circle A) because fundamentally it involves reflection about God. It seeks to understand God's mission, God's intentions and purposes, God's use of human instruments in God's mission, and God's working through God's people in God's world.6 Thus theology of mission deals with all the traditional theological themes of systematic theology-but it does so in a way that differs from how systematic theologians have worked down through the centuries. The difference arises from the multidisciplinary missiological orientation of its theologizing.

In addition, because of its commitment to remain faithful to God's intentions,

perspectives, and purposes, theology of mission shows a fundamental concern over

the relation of the Bible to mission. It attempts to allow Scripture not only to

provide the foundational motivations for mission, but also to question, shape,

guide, and evaluate the missionary enterprise?7

Second, theology of mission is "theology of" a specific missional context (circle C). In contrast to much systematic theology, here we are dealing with an applied theology. Because of its applicational nature theology of mission at times looks like what some would call pastoral or practical theology. This type of theological reflection focuses specifically on a set of particular is- sues-those having to do with the mission of the church in its context.

Theology of mission draws its incarnational nature from the ministry of Jesus, and always happens in a specific time and place. Thus circle C involves the missiological

use of all the social-science disciplines that help us under- stand the context

in which God's mission takes place. We begin by borrowing from sociology, anthropology, economics, urbanology,

the study of the relation of Christian churches to other religions, psychology,

the study of the relation of church and state, and a host of other cognate

disciplines to under- stand the specific context in which we are doing our

theology-of-mission reflection. Such contextual analysis moves us, secondly, to a more particular understanding of the context in terms of a hermeneutic of the setting in which we are ministering. This in turn, thirdly, calls us to hear the cries, see the faces, understand the stories, and respond to the vital needs and hopes of the persons who are an integral part of that context.

A part of this analysis today includes the history of the way the church in its mission has interfaced with a particular context down through history. The attitudes, actions, and events of the church's mission that occurred in that context prior to our particular reflection will color in profound and surprising ways the present and the future of our own missional endeavors. Thus we will find some scholars dealing with the history of theology of mission.8

While not especially interested in the theological issues as such, they are concerned about the effects of mission theology upon mission activity in a particular context. They will often examine the various pronouncements made by church and mission gatherings (Roman Catholic, Orthodox,

ecumenical, evangelical, Pentecostal, and charismatic) and ask questions, sometimes polemically, about the results for missional action.9

The documents resulting from these gatherings become part of the discipline of theology of

mission.

Third, theology of mission is specially oriented toward and for mission by the faith community (circle B). The most basic reflection in this arena is found in the many books, journals, and other publications dealing with the theory of missiology

itself.10 However, neither missiology nor theology of mission can be allowed to restrict itself to reflection only. As Johannes Verkuyl (1978, 6, 18) has stated, "Missiology may never become a substitute for action and participation. God calls for participants and volunteers in his mission. In part, missiology's goal is to become a 'service station' along the way. If study does not lead to participation, whether at home or abroad, missiology has lost her humble calling. . . . Any good missiology is also a

missiologia viatorum-'pilgrim missiology.'"

Theology of mission, then, must eventually emanate in biblically in- formed and contextually appropriate missional action. If our theology of mission does not emanate in informed action, we are merely a "resounding gong or a clanging cymbal" (1 Cor. 13:1). Intimate connection of reflection with action is absolutely essential for missiology. At the same time, if our missiological action does not itself transform our reflection, our great ideas may prove irrelevant or useless, and sometimes even destructive or counter- productive.

So the missional orientation that comes forth as a fruit of our theology of mission must translate into action. And missional action always occurs in a context. This brings us back to circle C-and our pilgrimage of mission-on- the-way begins again to reflect on a hermeneutic of the context, which in turn calls for a rereading of Scripture that flows forth into new missional insights and action.

One of the most helpful ways to interface reflection and action is by way of the process known as "praxis." Among the different understandings of this process,H Orlando Costas's

formulation (1976, 8) is one of the most constructive:

Missiology is fundamentally a praxeological phenomenon. It is a critical

reflection that takes place in the praxis of mission. . . . [It occurs] in the

concrete missionary situation, as part of the church's missionary obedience to

and participation in God's mission, and is itself actualized in that situation.

. . . Its object is always the world, . . . men and women in their multiple life

situations. . . . In reference to this witnessing action saturated and led by

the sovereign, redemptive action of the Holy Spirit, . . . the concept of

missionary praxis is used. Missiology arises as part of a witnessing engagement

to the gospel in the multiple situations of life,

to proclaim by word and deed

the coming of the kingdom of God

in Jesus Christ;

this task is achieved by means of the church's participation in God's mission of reconciling people'

to God, to themselves, to each other, and to the world, and gathering them into the church

through repentance and faith in Jesus Christ

by the work of the Holy Spirit

with a view to the transformation of the world

as a sign of the coming of the kingdom

in Jesus Christ.

The concept of praxis helps us understand that not only the reflection, but profoundly the action as well, is part of a theology-on-the-way that seeks to discover how the church may participate in God's mission in God's world. The action is itself theological, and serves to inform the reflection, which in turn interprets, evaluates, critiques, and projects new understanding in trans- formed action. Thus the interweaving of reflection and action in a constantly spiraling pilgrimage offers a transformation of all aspects of our missiological engagement with our various contexts.

The mission theologian takes the biblical text (circle A) utterly seriously.

It is equally true, as Johannes Verkuyl (1978, 6) has said, that "if study does not lead to participation,

. . .

missiology has lost her humble calling." Thus we find that theology of mission is a process of reflection and action involving a movement from the biblical text to the faith community in its context. By focusing our attention on an integrating theme, we encounter new in- sights as we reread Scripture from the point of view of a contextual hermeneutic. These new insights can then be restated and lived out as biblically in- formed, contextually appropriate missional actions of the faith community in the particularity of time, worldview, and space of each context in which God's mission takes place.

Mission Theology as Analytical

the mission enterprise is complex enough just in terms of its practice. It be-

comes more complex when we begin to examine the host of theological assumptions, meanings, and relations that permeate that practice. For this reason, mission theologians have found it helpful to partition their task into smaller segments. We noticed that Gerald Anderson's definition of mission uses the terms "faith, motives, message, methods, strategy, and goals." Similarly, in analyzing Eastern Orthodox Mission Theology Today (1987) James Stamoolis organizes his work around "the historical background, the aim, the method, the motives, and the liturgy" of mission as it takes place among and through the Eastern Orthodox.

However, there is another way in which mission theologians have classified the various aspects of their task. This method stresses the fact that mission is missio Dei-it

is God's mission. So one finds mission theologians asking about God's mission (missio Dei),12 mission as it occurs among humans and utilizes human instrumentality (missio hominum), missions as they take many forms through the endeavors of the churches (missiones ecclesiarum),13 and mission as it draws from and impacts global human civilization (missio politica oecumenica).14

The missio Dei, which is singular, is pure in its motivation, means, and goals, for it derives from the nature of God. The missio hominum is simultneously just and sinful, related to fallen humanity, and always mixed as to its motivations, means, and goals. The missiones ecclesiarum are plural be- cause of the multiplicity of the activities of the churches, the lack of unity among them, and the mixture of centripetal (gathering) activities with centrifugal (sending) activities; another factor is that their shape is heavily influenced by what is going on within the churches and the Christians who form them. Finally, the missio politica oecumenica pertains to God's concern for the nations, God's interaction through God's people with the civilizations, cultures, politics, and human structures of this world, and the way Christ's kingdom mission always calls into question the kingdoms of this world.

These are important distinctions. And a final one needs to be made. Mission is also both missio futurorum and missio adventus. Missio futurorum has to do with the predictable results of God's mission as it takes place in human history. Thus missio futurorum extrapolates into the future the natural human results of the missions of the churches in the midst of world history. But the story of mission is incomplete if it stops there. We must also include missio adventus. Adventus is the inbreaking of God, of Jesus Christ in the in- carnation, of the Holy Spirit at Pentecost, of the Holy Spirit in and through the church. Missio adventus is, then, God's mission as it brings unexpected surprises, radical changes, new directions, almost unbelievable transformation in the midst of human life: personal, social, and structural. God works in the world through both missio futurorum and adventus.

And in sorting out the theological issues of mission theology the mission

theologian needs constantly to be asking about their difference and their interrelation.

Once we have seen the two ways of classifying the aspects of mission theology, we will want to bring the two systems together. I have attempted to do this in a "Working Grid of Mission Theology" (see Figure 9). Notice that at each horizontal level of the grid there are at least five different types of questions to be asked; for example, in regard to the motives of mission, there are God's motivation, human motivation, the motivations of the churches, motivations in relation to global civilization, and motivation in terms of

missio futurorum as distinguished from adventus. Notice also that one can work vertically, asking, for example, how missio Dei, in contrast with the other vertical columns, informs the motives, means, methods, and goals of mission. Clearly no one missiologist can do all that is represented by this grid. That is not necessary. Only one or two of the many boxes may represent the area to investigate in a particular context at a particular moment and in relation to specific actions of mission. However, I have been discovering that the grid can both offer us simplicity of analysis by differentiating the topics to explore and point to the complexity of the whole enterprise. My students and I have begun to see that almost every master's thesis or doctoral dissertation in missiology naturally falls primarily into one of the squares. Yet when the re- searcher begins to reflect in terms of mission theology as related to that one

Mission Theology as Definitional

One of the most crucial yet frustrating tasks of mission theology is to assist missiology in defining the terms it uses. And within this enterprise the most central question has to do with how one may define "mission" itself. What is mission? and what is not mission? The reader will notice that nearly every chapter in this book will deal in some way or other with this question and its implications.

For the sake of brevity, and in the hope of helping the reader more fully understand subsequent chapters, let me offer my own preliminary definition of mission:

Mission is the people of God intentionally crossing barriers from church to non-church, faith to non-faith,

| Missio | Missio | ||||

| Missio | Missiones | Politica | Futurorum/ | ||

| Missio Dei | Hominum | Ecclesiarum | Oecumenica | Adventus | |

| Mission | |||||

| Context | |||||

| Agents of | |||||

| Mission | |||||

| Motives of | |||||

| Mission | |||||

| Means of | |||||

| Mission | |||||

| Methods of | |||||

| Mission | |||||

| Goals of | |||||

| Mission | |||||

| Results of | |||||

| Mission | |||||

| Centripetal! | |||||

| Centrifugal | |||||

| Activities | |||||

| Utopia/Future | |||||

| Hope | |||||

| Presence | |||||

| Proclamation | |||||

| Persuasion | |||||

| Incorporation | |||||

| Structures | |||||

| Partnerships | |||||

| Power | |||||

| Prayer | |||||

| Praise | |||||

| Other? | |||||

Figure 9

Working Grid of Mission Theology

narrow area, the investigation leads naturally to questions about many of the other areas represented by the grid.

Mission Theology as Truthful

In the social sciences, and in fact in all scholarly enterprises, one of the most important questions has to do with the basis On which One can determine the

validity and reliability of one's investigation. In the social sciences that have heavily impacted missiology, normally the concept of validity has to do with the question, "How can we be sure that we are collecting the right data in the right way?" The concept of reliability, on the other hand, is understood to address the question, "How can we be sure that if the same approach were taken again, the same data would be discovered?"

However, in evangelical mission theology these questions are not the right ones. For the mission theologian is not particularly concerned about the

quality of the empirical data nor the repeatability of the process so as to yield identical results. In fact, the opposite is true. Given that the mission theologian studies God's mission, the data should always be new (and will sometimes call into question earlier data), and the results should often be surprising.

Evangelical mission theology, therefore, offers a particular way of recognizing acceptable research. The question of validity must be transformed into one of trust, and the matter of reliability must be seen as one of truth. Thus these are the two major groups of methodological questions facing the mission theologian:

Trust

Did the researcher read the right authors, the accepted sources?

Did the researcher read widely enough to gain a breadth of perspectives on the issue?

Did the researcher read other viewpoints correctly?

Did the researcher understand what was read?

Are there internal contradictions either in the use (and understanding) of the authors or in their application of the issue at hand?

Revelatory-Acceptable mission theology is grounded in Scripture. Coherent-It

holds together, is built around an integrating idea. Consistent-It has no

insurmountable glaring contradictions, and is consistent with other truths known about God, God's mission, and God's revealed will.

Simple-It has been reduced to the most basic components of God's mission in terms of the specific issue at hand.

Supportable-It is logically, historically, experimentally, praxeologically affirmed and supported.

Externally confirmable-Other significant thinkers, theological communities, or traditions lend support to the thesis being offered. Contextual-It interfaces appropriately with the context. Doable-Its concepts can be translated into missional action that in turn is consistent with the motivations and goals of the mission theology

being developed.

Transformational-The carrying out of the proposed missional action

would issue in appropriate changes in the status quo that reflect biblical

elements of the missio Dei.

Productive of appropriate consequences-The results of translating the concepts into missional

action would be consistent with the thrust of the concepts themselves, and with

the nature and mission of God as revealed in Scripture.

Truth

Is there adequate biblical foundation for the statements being affirmed? Is

there an appropriate continuity of the researcher's statements with theological

affirmations made by other thinkers down through the history of the church?

Where contradictions or qualifications of thought arise, does the mission theologian's work adequately support the particular theological directions being advocated in the study?

Are the dialectical tensions and seeming contradictions allowed to stand, as they should, given what we know and do not know of the mystery of God's revealed hiddenness as it impacts our understanding of missio Dei?

Theology of mission is prescriptive as well as descriptive. It is synthetic (bringing about synthesis) and integrational. It searches for trustworthy and true perceptions concerning the church's mission that are based on biblical and theological reflection, seeks to interface with the appropriate missional action, and creates a new set of values and priorities that reflect as clearly as possible the ways in which the church may participate in God's mission in a specific context at a particular time.

When mission theology is abstracted from mission practice, it seems strange and too far removed from the concrete places and specific people that are at the heart of God's mission. Mission theology is at its best when it is intimately involved in the heart, head, and hand (being, knowing, and doing) of the church's mission. It is a personal, corporate, committed, profoundly transformational search for always new and more profound understanding of the ways in which the people of God may participate more faithfully in God's mission in God's world.

These methodological questions lead to specific criteria to evaluate whether the result of mission theology's work as it interfaces with missiology is acceptable:

1. I see the two terms "theology of mission" and "mission theology" as interchangeable. However, I am beginning to find "mission theology" more appropriate than "theology of

mission." In the introduction I will use "theology of mission," particularly in

the section on the integrative function of the discipline. But "mission theology" will increasingly become the dominant term in this volume.

2. Anderson attributes this phrase to the 1963 Mexico City gathering of the Commission on World Mission and Evangelism/World Council of Churches. See Orchard 1964, 175.

3. The list of cognate disciplines from which missiology draws to describe, understand, analyze, and prescribe the complex nature of mission is long. Those represented in the diagram are only illustrative. A more complete list might include biblical studies, church history, mission history, systematic theology, contextualization, cultural anthropology, linguistics and translation, sociology, the study of other faiths, dialogue with other faiths, studies of women in mission, sociology of religion, social psychology, urban studies/anthropology and sociocultural analysis of the city, socioeconomic and political analysis, ecumenics and studies of the world church, statistics and futurology, evangelism, the history of evangelism, church growth, studies of missionary congregations, dynamics of cross-cultural communication, relief and development, discipleship, spirituality and spiritual formation, leadership formation, structures for mission, mission administration, theological education, congregational renewal, history of revivals, cross-cultural counseling, preaching, the missionary family, psychological issues of many types, ecclesiastics and the relationship of churches, mission organization, mission funding, mission promotion/recruitment/personnel, the relation of church and state, nominalism and secularization, and othsers.

4. Missiologists have differed in the integrating idea or phrase they have chosen to use as the center of their missiology. Examples of integrating ideas would include the conversion of the heathen, the planting of the church, and the glory of God (Gisbert Voetius), the Great Commission (William Carey), the lostness of humanity (Pietism), the praise of God (Orthodox missiology), the people of God (Vatican II), making disciples of panta ta ethne (Donald McGavran), the God of history, God of compassion, God of transformation (David Bosch), the kingdom of God (Arthur Glasser), and humanization (the World Council of Churches), Among other integrating concepts are the pain of God, the cross, bearing witness in six continents, ecumenical unity, the covenant, and liberation,

5. The three-arena nature of missiology is not original with me. A number of others, particularly those who deal with contextualization from a missiological perspective, have highlightedsomething similar. See, e.g., Nida 1960; Miguez-Bonino 1975; Coe 1976; Conn 1978; 1984; 1993a; 1993b; Hiebert 1978; 1987; 1993; Glasser 1979b; Kraft 1979; 1983; Kraft and Wisley 1979; Fleming 1980; Coote and Stott 1980; Schreiter 1985; Branson and Padilla 1986; Tippett 1987; Luzbetak 1988; Shaw 1988; Gilliland, ed., 1989; Hesselgrave and Rommen 1989; San- neh 1989; William A. Dyrness 1990; Bevans 1992; and Jacobs 1993.

6. See, e.g., Niles 1962; Vicedom 1965; Taylor 1973; Verkuyl 1978, 163-204; and Stott 1979.

7. See, e.g., Glover 1946; G. Ernest Wright 1952; Gerald H. Anderson 1961; Boer 1961; Blauw 1962; Allen 1962a; George Peters 1972; Costas 1974a; 1982; 1989; De Ridder 1975; Stott 1975b; J. H. Bavinck 1977; Newbigin 1978; VerkuyI1978, ch. 4; Bosch 1978; 1991; 1993; Gilliland 1983; Van Rheenen 1983; William A. Dyrness 1983; Senior and Stuhlmueller 1983; Hedlund 1985; Spindler 1988; Gnanakan 1989; Glasser 1992; and Van Engen 1992b; 1993. A combined bibliography drawn from these works would offer an excellent resource for examining the relation of the Bible and mission.

8. See, e.g., Bassham 1979; Bosch 1980; Scherer 1987; 1993a; 1993b; Glasser and McGav- ran 1983; Glasser 1985; Utuk 1986; Stamoolis 1987; and Van Engen 1990.

9. See, e.g., McGavran 1972a; 1972b; 1984; Johnston 1974; Hoekstra 1979; Hedlund 1981; and Hesselgrave 1988. One of the most helpful recent compilations of such documents is Scherer and Bevans 1992.

10. Examples of some readily accessible works include Sundkler 1965; J. H. Bavinck 1977; Verkuyl1978; Bosch 1980; 1991; Padilla 1985; Scherer 1987; Verstraelen 1988; Phillips and Coote 1993; and Van Engen et al. 1993. Clearly the most comprehensive work, which will be considered foundational for missiology for the next decade, is Bosch 1991.

11. See, e.g., Robert McAfee Brown 1978, 50-51; Vidales 1979, 34-57; Spykman et al. 1988, xiv, 226-31; Schreiter 1985,17,91-93; Costas 1976, 8-9; Boff and Boff 1987, 8-9; Scott 1980, xv; Leonardo Boff 1979, 3; Ferm 1986, 15; Padilla 1985, 83; Chopp 1986, 36-37, 115- 17,120-21; Gutierrez 1984a, 19-32; 1984b, vii-viii, 50-60; and Clodovis Boff 1987, xxi-xxx.

12. Georg Vicedom brought the term missio Dei to the attention of the world church before and during the 1963 Mexico City meeting of the Commission on World Mission and Evange- lism/World Council of Churches. See his Mission of God (1965).

13. The discussion in conciliar circles over whether to use "mission" or "missions," and the subsequent change in the name of the International Review of Missions to International Review of Mission, were the fruit of confusion between God's mission, which is one, and the enterprises of the churches ("missions"), which are many.

14. See, e.g., VerkuyI1978, 394-402.